Freya Najade

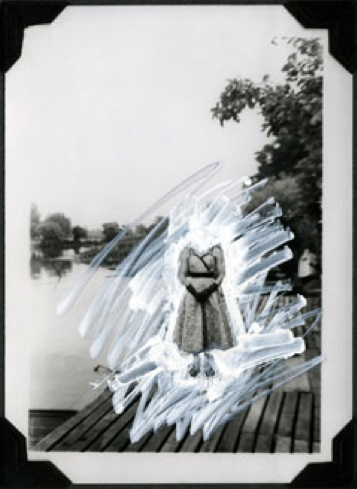

Freya Najade is a German photographer working in London. Her sensitive and poignant way of seeing beauty in the mundane transforms the everyday.

Freya’s work Strawberries in Winter and Jazorina have been nominated for the fifth and sixth cycle of Prix Pictet, respectively. Her first monograph Jazorina was published by Kehrer Verlag in May 2016 and her second book Along the Hackney Canal by Hoxton Mini Press in September 2016. Here she offers some advice from her experiences in publishing and talks about her relationship with photography in a wider sense.

Tell us a bit about how you came to photography. How did you find it and what does it mean to you?

Photography means a lot to me, it’s definitely one of the most important things in my life. Going out and taking pictures can make me profoundly happy. The photography industry as a whole can be sometimes daunting, but the process itself – the act of photographing – I truly love!

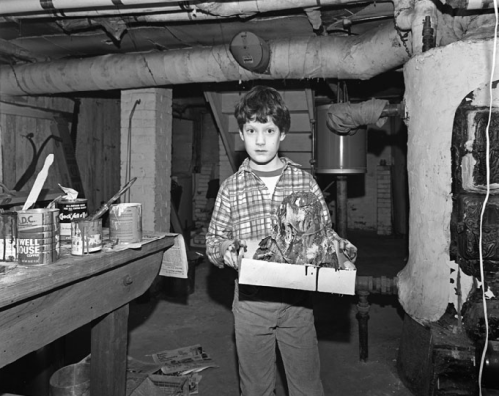

I liked photography from when I was very young, but I discovered my real passion for taking pictures in my twenties when my father gave me one of the first digital cameras – I just started shooting away. I was actually studying to become a special needs teacher at the time. After I graduated as a teacher I went to the US and lived for a year in San Francisco where I took photography classes at the City College. Their system was quite structured and I had to start with black and white classes: photographing in black and white, learning to develop my own film, studying about the history of photography… I realized then that I love colour photography and that I wanted to do photography professionally.

How would you describe your wider practice?

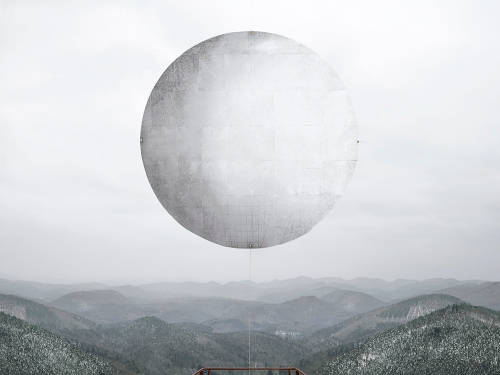

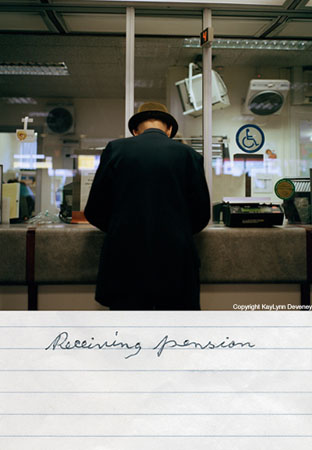

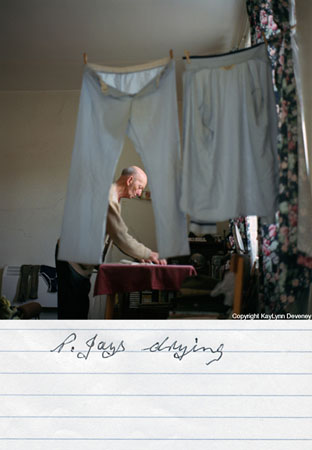

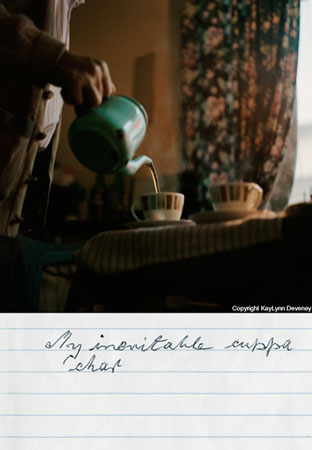

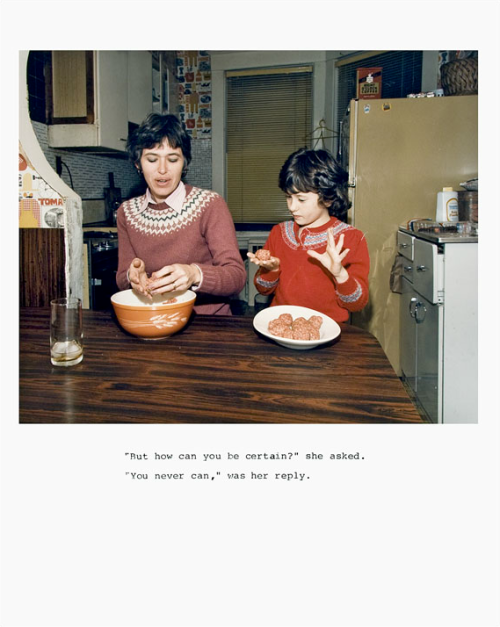

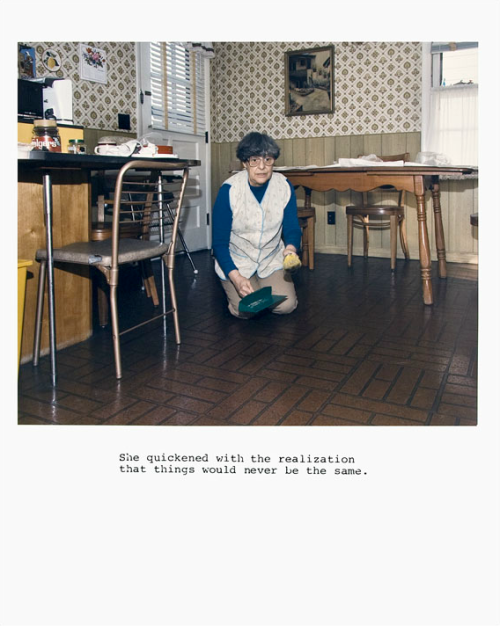

I divide my time doing commercial work and working on long-term personal projects, which allow me to capture certain topics in more depths and visually intriguing ways. My personal work lies somewhere within the genre of documentary photography. The themes I work on vary and are mostly quite different from each other. They range from old age to food production; my most recent work is about the Canals in Hackney, London. My approach and visual language evolve when working on a project, it all depends very much on the topic, how I perceive it and what I would like to bring across.

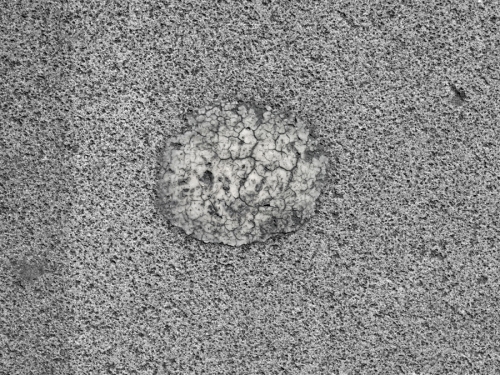

What attracted you to the canal as subject matter? What resonated with you about it?

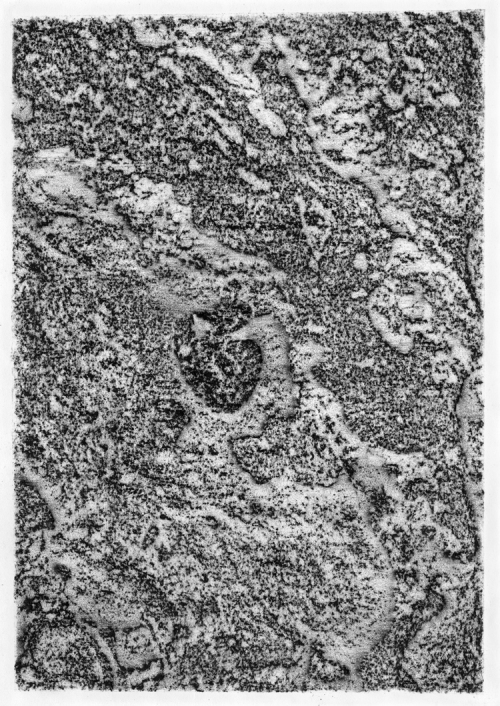

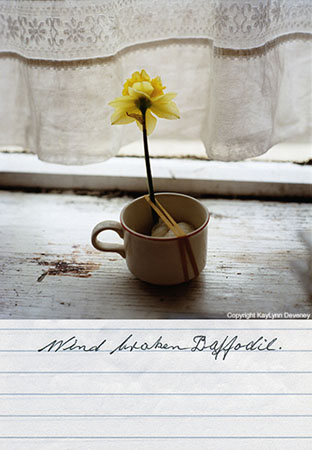

To me the beauty of this area is very different to the picturesque English gardens and parks, or the pristine, uncivilised nature of oceans, mountains and forests. The landscape along the Hackney Canal seems to be indecisive between civilisation and wilderness, trimness and grittiness, vital beauty and gloominess. I love these juxtapositions and at times overlays.

Is this series in any way metaphorical? How so?

I didn’t photograph this series with metaphorical intentions but certain images probably lead to metaphorical interpretations.

What was it like working with the publisher? What aspects to the overall production did this relationship bring? What would you advise artists to look for when working with publishers from your experience?

My experience to work with Hoxton Mini Press has been great. The whole process to make this book has been very easy and actually a lot of fun. After the first meeting we all agreed that we would like to do this book. At that point I wanted to shoot more and over the following months we continued to meet up to look at my new images and began to shape the book. And again it went very smooth, we agreed very quickly on favourite photographs, the title, the front cover and on the sequencing of the images in the book.

Below a few points I would advise to find out before publishing a book with somebody:

- Who is the audience of the publisher? Do you feel your book fits in their program?

- Do you like the design and feel of the other photo books of the publisher?

- What kind of network has the publisher in terms of distributing their books, press, showing their books in photo festivals, and size of mailing list?

- Do you have to financially contribute to the production of your book?

- What are you getting out of publishing with them? What has the publisher to offer to you?

What are the most rewarding, and most challenging things about being a photographer? How do you make it work?

As mentioned above the most rewarding thing is for me the process of photographing itself. I love to explore and wander around and to look closely at my surroundings. I find this in itself already truly enjoyable. If, then, I discover a view, or an object or person who or which I find special and if, then, all the rest comes together: the light, the angle, the colours, the expression, and everything just feels right, those are the moments that keep me going.

Of course it is also rewarding, when others recognize your work either by telling you or by publishing it, exhibiting it, or by commissioning you.

The most challenging thing as a photographer is probably to continue doing your own work and to make money. Since my Masters I have done various assignments, I have worked on editorial stories and portraits for magazines and have also covered different events for clients such as Burberry and Google. In recent years I have increasingly worked on architectural photography commissions. I have always loved architecture, and I also really enjoy documenting it. So eventually, together with Marcela Spadaro – who worked as an architect for or 10 years – I have founded NAARO, an architectural photography studio.