Karen Knorr is a photographer with international acclaim who came to prominence in the 1980s through her work ‘Gentlemen’ and ‘Belgravia’ which are currently on display at Tate Britain until October 2015. Her early work was heavily influenced by film theory and the politics of representation. An extensive list of exhibitions and lecturing roles include Tate Modern, Tate Britain, Harvard, University of Westminster and Goldsmiths. She is currently a Professor of Photography at UCA, Farnham.

Here she talks with me about her life and work. This interview was commissioned for Photomonitor.

__________

Sharon Boothroyd: You were somewhat of an insider to this world (Belgravia) via your parents if I am correct. Can you describe your relationship to Belgravia before you made this work?

Karen Knorr: I arrived in London from Paris on July 4, 1976. My parents had just purchased a 25-year lease for a maisonette (two floor apartment) at Lowndes Square in Belgravia. I lived in Belgravia for a short period, 6 months, while I was applying for photography courses to build a portfolio of photographs that I could show photographers such as David Bailey. I came to London with a series of street photographs and surrealist- inspired photographs made in Paris as an art student but realised I needed more depth to the work.

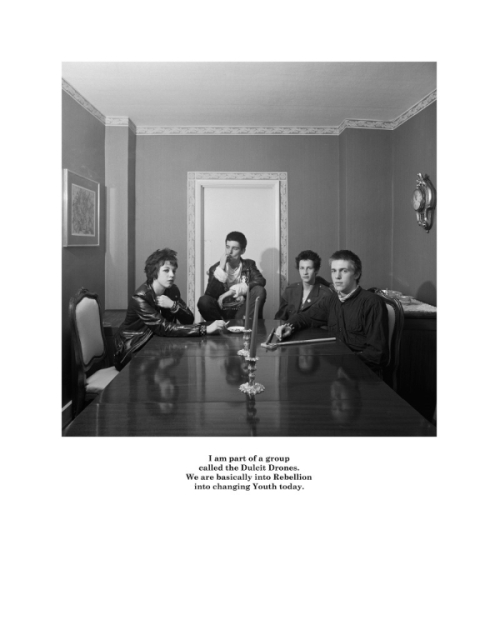

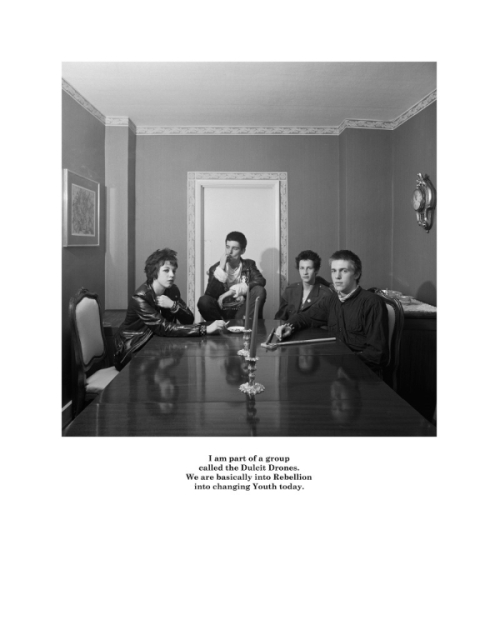

I was offered a place on a part time professional photography course at Harrow College of Technology and Art and it was here that I began to use a 5 x 4 plate camera. It was also on this course that I met Olivier Richon with whom I photographed Punks in several music clubs in London, published as a book by Gost in 2012.

I quickly decided that Belgravia was not where I wanted to live and definitely not with my parents! I moved out in January 1977 sharing a house with friends at Narcissus Road in West Hampstead. The commute to Harrow was easier and this allowed me the creative freedom necessary to explore Punks. (Showing as part of group exhibition We could be Heroes at The Photographers’ Gallery Print Sales, 6th Feb – 12th April 2015.)

At Harrow College one of my tutors Rosie Thomas introduced me to Camerawork, a new magazine published in East London that had published critical writings on photography with artists and activists such as Jo Spence. This was a different perspective from Creative Camera, a magazine edited by Colin Osman and Peter Turner which seemed more in tune to the aesthetics prevalent in Fine art photography championed by John Szarkowski at the MOMA.

My outlook and ideas concerning photography changed. I became interested in a critical approach (rather than self-expressive) to photography and began to look for a B.A. Honours course. The Polytechnic of Central London, School of Communication, at Riding House Street accepted me as a B.A. Hons in Film and Photographic Arts in 1977.

Interesting how you differentiate a critical approach from a self-expressive one. Could you expand on what the difference is?

The difference is that self-expressive work revolves around a concern for the individual ego of the artist/ photographer. It comes out of a Romantic view of the artist as having a unique and privileged view on the world suffused with authentic emotions that can be directly transferred onto the work. This notion of subjective authenticity was challenged by writers and philosophers such as Roland Barthes (Death of the Author) and also challenged by the theoretical writings of Victor Burgin in the 1970s.

A critical approach may deal with emotion and desire but more knowingly appreciates the staging and performing involved. In other words that something has to be constructed…performed.

Why did you want to make the Belgravia work? What instigated it and how did you approach your subjects?

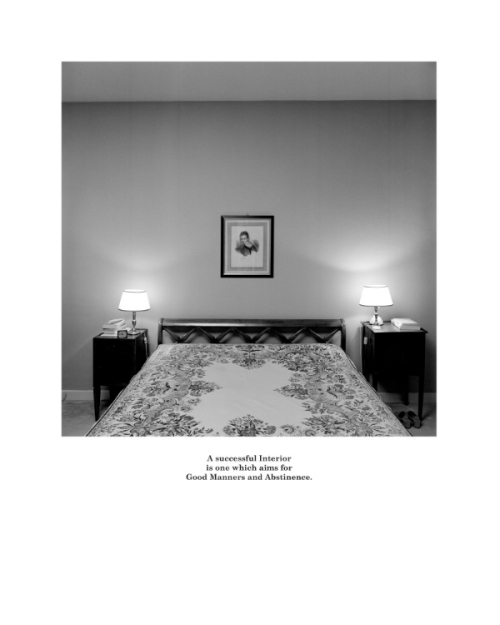

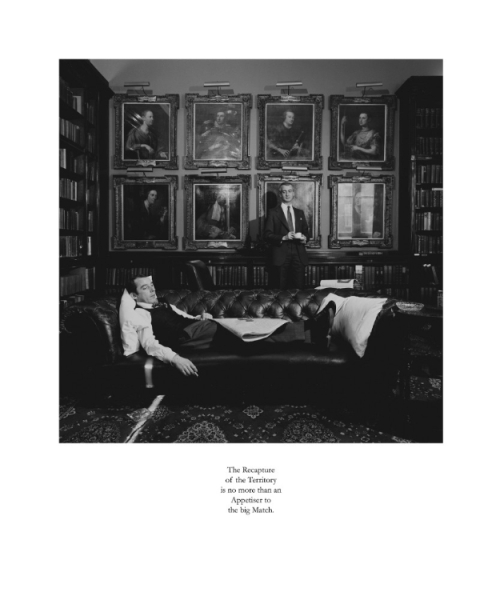

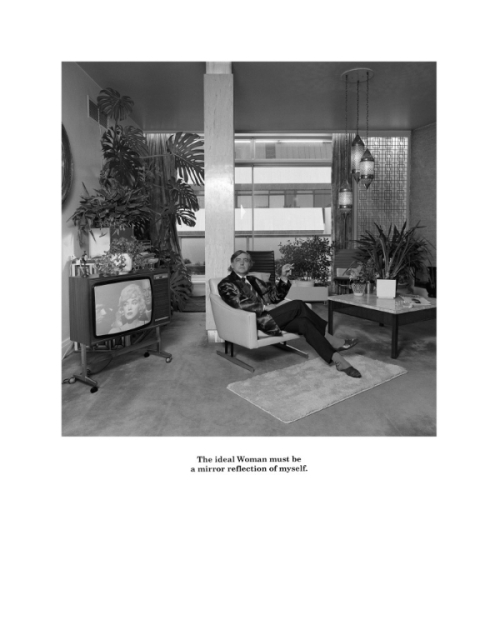

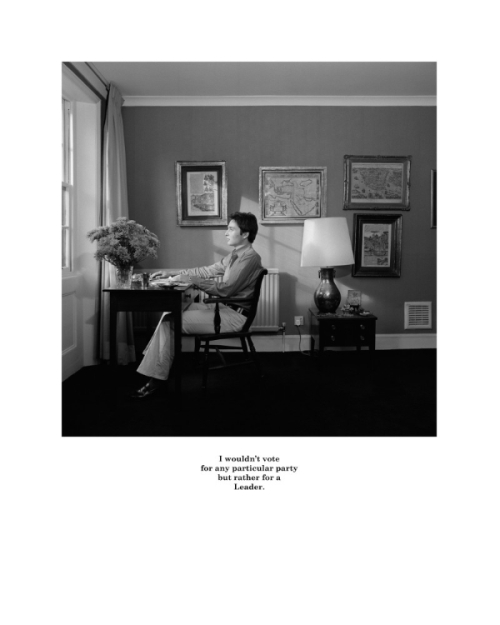

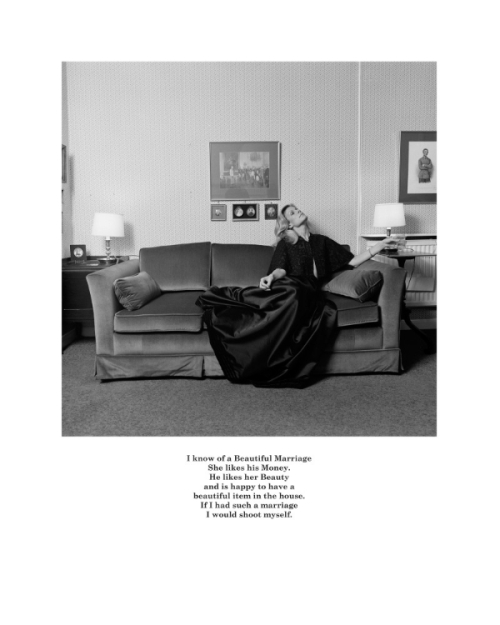

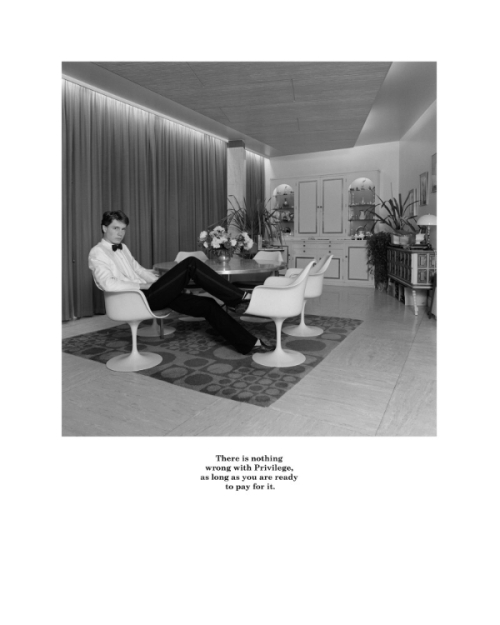

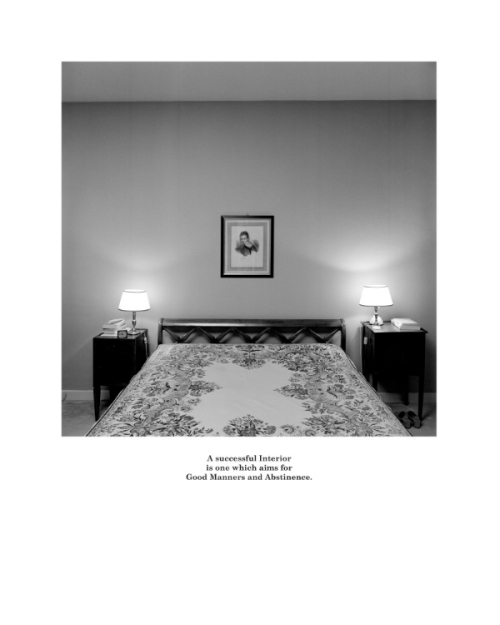

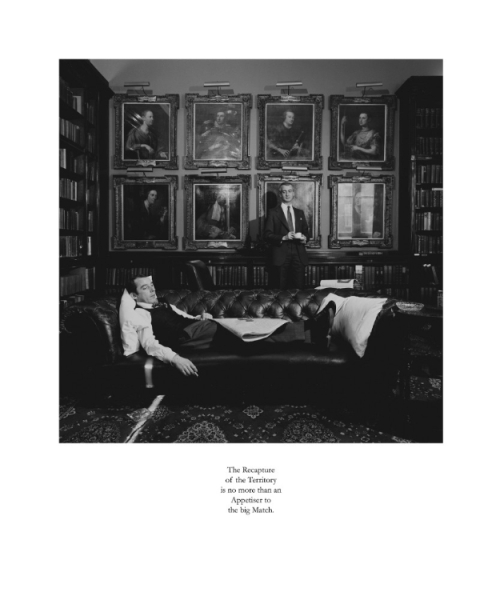

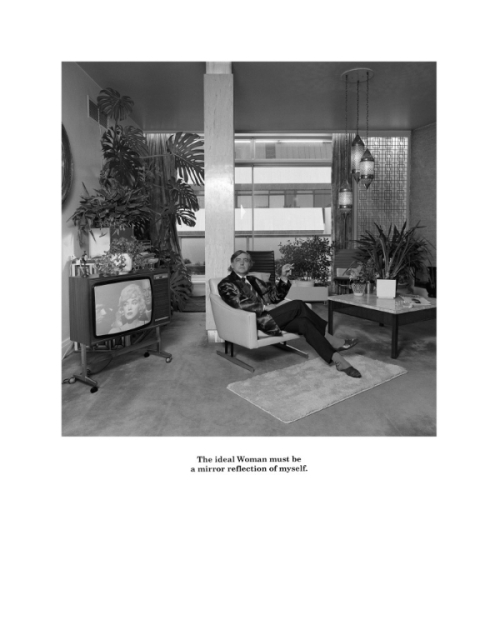

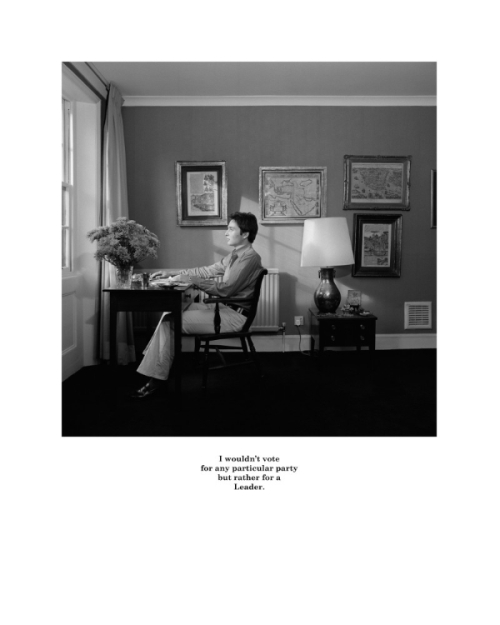

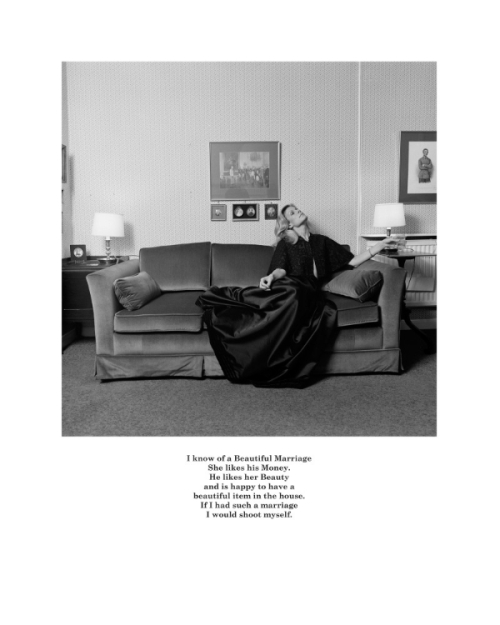

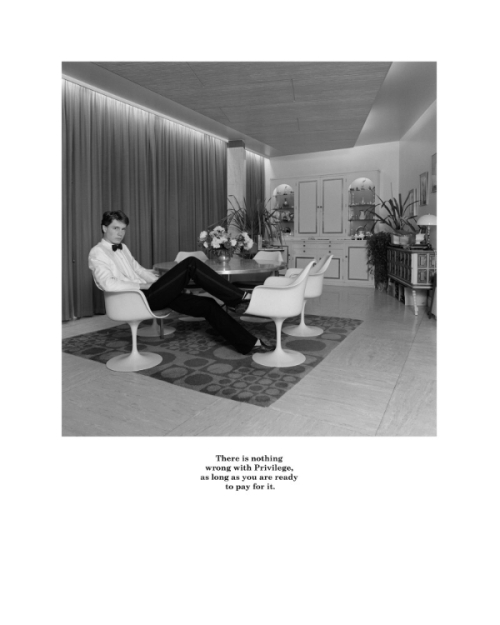

Belgravia (1979-1981) was a series of environmental portraits on social class and the received opinions of the wealthy who lived in Belgravia, an area near Harrods (London) which now has some of the most expensive real estate in the world.

The work is autobiographical and uses humour (which operates in the space between text, image and viewer) in order to reconsider class and its prejudices. It also focuses on social inequality between men and women as well as the aspirational values attached to ‘taste’. The third meaning, a concept developed by Roland Barthes when considering montage (editing), interested me and I had read the collection of essays in Image Music Text during my second year at the Polytechnic of Central London (PCL) photography course. Belgravia arose out of an awareness of this effect between image and text that had been developed by conceptual artists such as Victor Burgin (who was my tutor) but also an awareness of Walker Evans, Diane Arbus, Bill Brandt and Bill Owens’ work. The texts were constructs, highlighted by their arrangement and design beneath collaborative portraits of my parents and their friends. I would stage and style the portrait choosing and arranging furniture and clothes with the sitters. Using a 500 CM Hasselblad and a Balcar Flash with reflective umbrellas, this process was a lengthy one that would take up to three hours. I wrote down quotes from our conversations together and these were then edited and typeset on lithography film.

Bill Owens (whose book Suburbia (1) influenced my work) visited the Polytechnic of Central London during my second year on the BA Honours Photography course and we had a lively debate later in the pub about the nature of photography, whether to photograph things as they were found (his point of view) or to construct and rearrange the situation (my point of view).

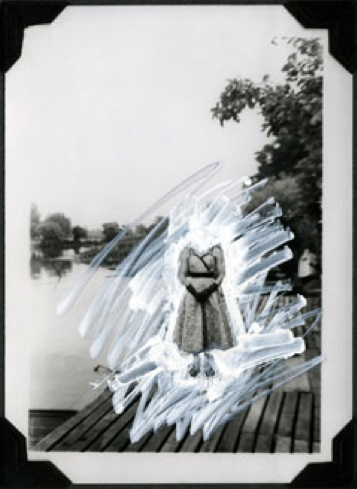

The first image I took in the series was of my mother and grandmother at Lowndes Square, smoking and drinking in furs, accompanied by Belle de Jour (Buñuel 1967) on television which starred Pierre Clémenti kissing Catherine Deneuve. The portrait is performed and collaborative, photographed with bounced flash.

I approached my subjects as ‘the girl next door, aspiring photographer’ and spent hours visiting my subjects who were introduced through a network of my parents’ friends and acquaintances that lived in Belgravia. The quotes taken from their conversations were carefully edited and designed, printed onto the actual surface of the photograph. The idea was to prolong the viewing of the photograph using the aesthetics of fine art photography. The text brings a new reading to the image and the humour operates according to the spectator’s cultural background.

In the Belgravia series I was also interested in referencing architectural photography that could be found published in House and Gardens magazine. Interested in the semiotics of the bourgeois domestic interior I wanted to highlight taste and lifestyle in a humorous and ironic way by structuring the viewpoint and using text.

There was also a critical engagement with portraiture and the emerging celebrity culture found in such magazines as Tatler and Vogue that I wished to challenge. I was very aware of the art context and wished to challenge the male dominated art photography world; especially the white male photojournalist who used ‘fixers’ to gain access to developing world cultures.

This early work was critical documentary form that engaged with what was closest to me: my own family and friends. It was only much later in the 1990s that I began to work in Europe and only since 2008 that I ventured into a new digital world in my recent India Song series.

What do you think your relationship to the subjects and your understanding and awareness of the place brought to the final outcome?

The attitudes depicted through image and text were ones I did not share and the irony is strong, at moments almost cutting. These are attitudes that surrounded me in my youth and could have become my own. The first person ‘I’ in the photographs inflects an autobiographical element yet I was not aspiring to similar values. Yet all these texts could have been me.

Did your feelings towards the place change as a result of making this work?

This work is about class and privilege and the insouciance of having it. I was part of the problem, part of this world and felt conflicted.

How did you gain access to the gentlemen’s clubs when by their very nature they excluded women?

By chance and luck. It took me a year to gain access to more than one club. I spoke about my problems accessing gentlemen’s clubs to a man who ran a sandwich bar across the road from the PCL in Riding House Street showing him some contacts of other work. It turned out that his friend was Lucius Cary, 15th Viscount Falkland. Finally I gained permission to photograph the Turf and Brooks through the help of Lucius Cary. The irony was that he was Viscount of Falkland and the work highlights the conflict in the Falklands among other themes. Lucius was totally supportive and even posed for a portrait in the series, leaning over a wrought iron balustrade overlooked by a marble bust of Pitt the Younger (Britain’s youngest prime minister).

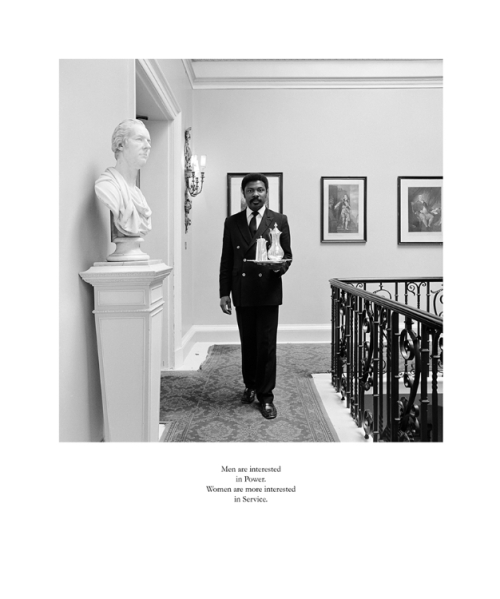

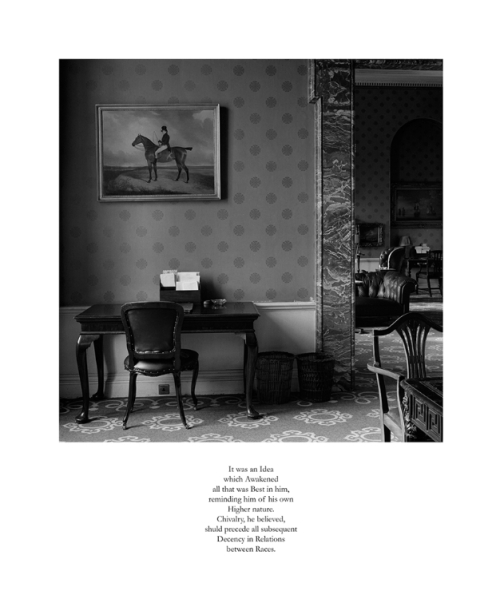

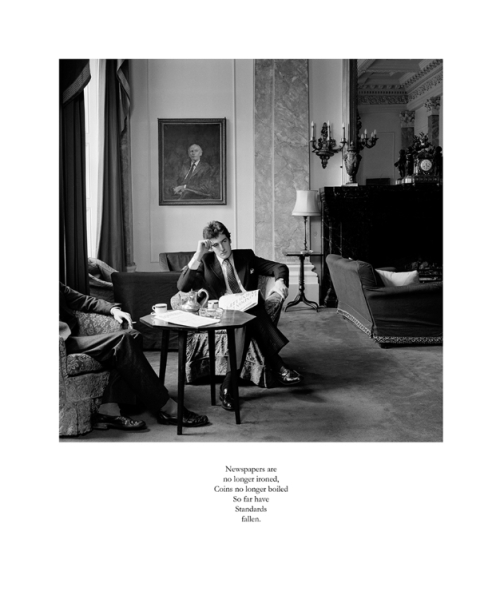

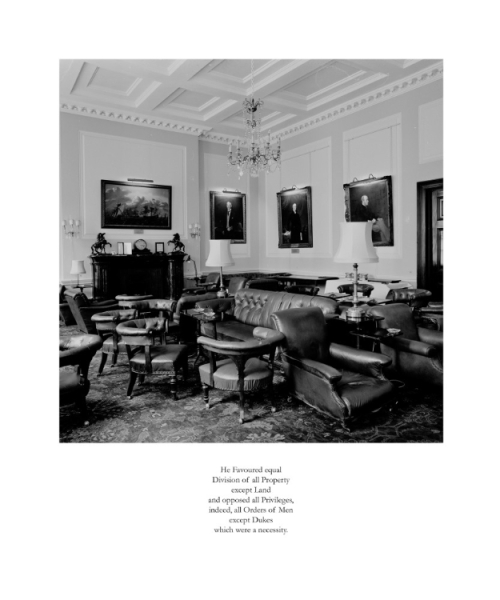

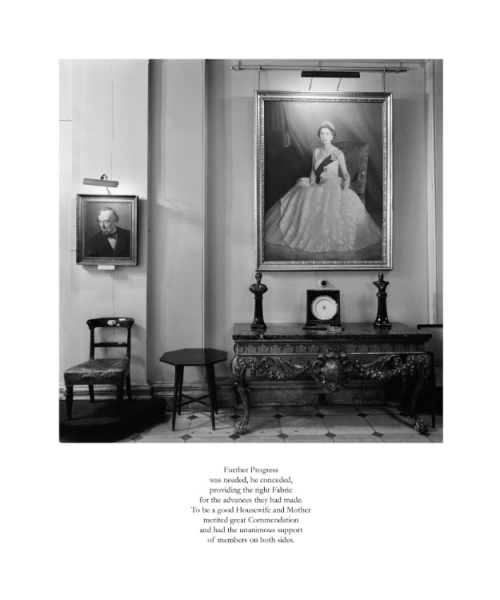

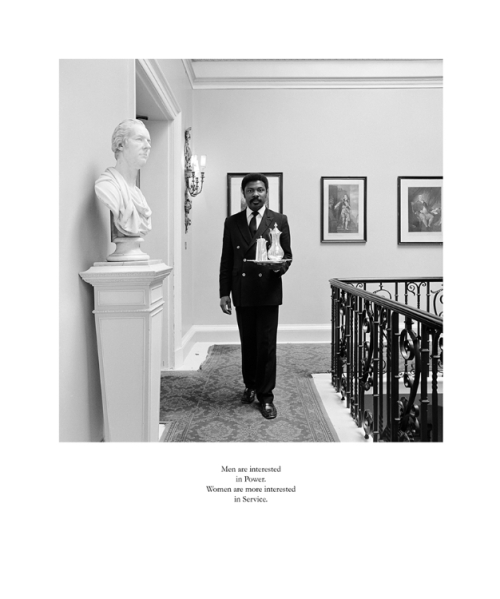

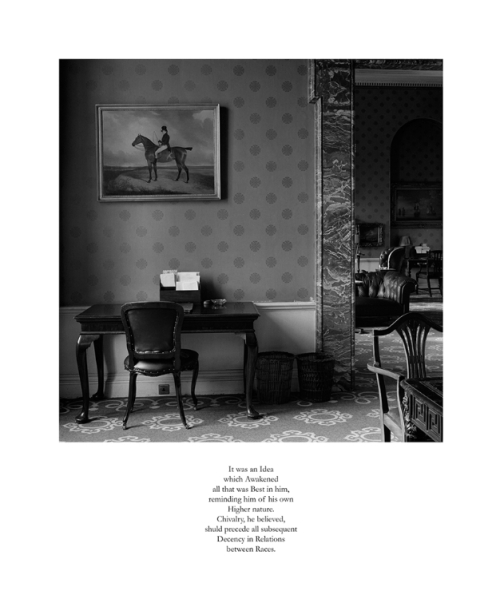

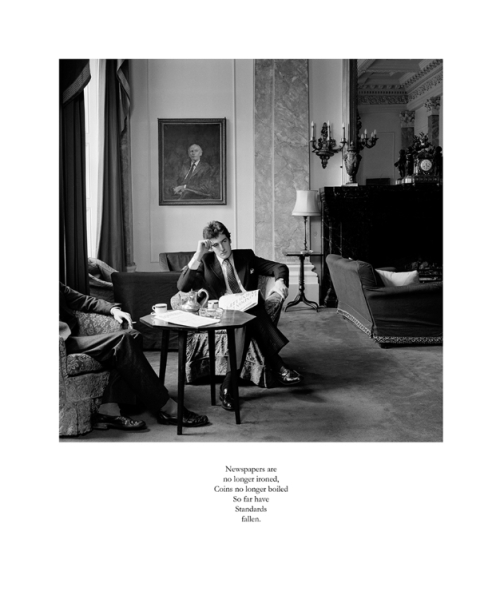

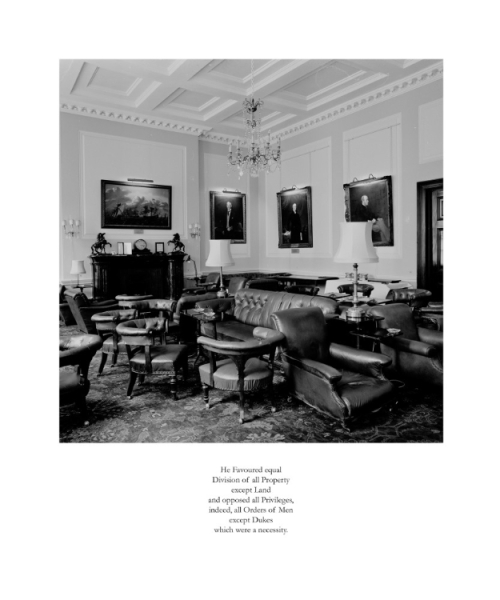

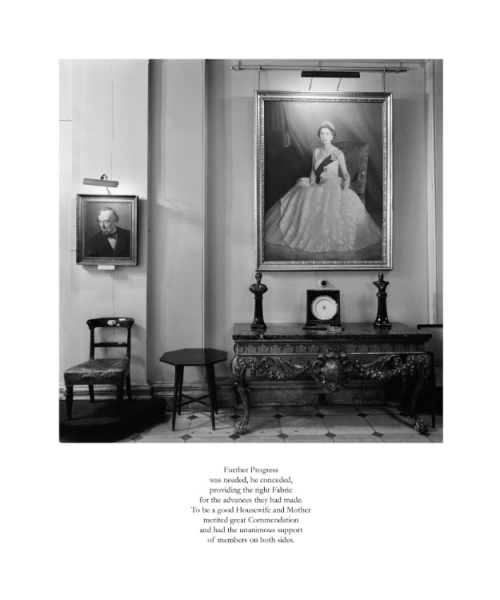

Gentlemen includes empty interiors and staged portraits of club members and actors/ friends. The text is entirely fictional, composed in two voices: the past tense historical voice and the present tense. Under the images of men photographed, the voice is in the present tense, yet referencing change; the end of the British Empire, how things once were. Under the empty interiors the voice is in the past tense… the past and the present alternate. I was reading speeches of parliament that used to be published in The Times newspaper (Hansard) and Boy’s Own stories of adventure and spy novels.

Gentlemen was very much about patriarchal values and the nature of power in the political centre of London, not far from Westminster and the palace. Language and its inflections become powerful in how they include and exclude, turning people into ‘them’ and ‘us’. The fetishisation of English with its sense of superiority is with us today; disseminated across the British Empire it has become the global language of trade.

Capitalised letters performed a parody of Englishness situating it in the 18th century tradition of satire (Pope and Swift). The first clubs founded as coffee houses were places of dissent where discussions were held with the aim of changing the British mindset, inspiring it to move forward into an era of true enlightenment and moral virtue. Thatcherite Britain appalled me with its jingoist drive towards war in the Falklands. There was cross party support for war and very little dissent. Only one journalist stood out in this respect in the mainstream press, James Cameron, who wrote for The Guardian. Other exceptions to the prevailing pro-war hysteria were John Pilger and Noam Chomsky.

How did they receive you when you were in? Would you describe this work as collaboration?

They were polite and helpful and let me get on with it. I would ask people who worked in the clubs such as the porter and secretary to pose for me in different rooms where I would set up flash equipment. This work was collaborative as it was staged and performed between us. I also used friends as actors who dressed the part. By directing I was challenging the power relations between women and men in the club interior. In clubland, women and black people are invisible and have restricted access to certain rooms; I took liberty to transgress those roles by using the camera as a tool.

Despite equal rights legislation passed in the 1970s many clubs did not allow full membership to women. Margaret Thatcher, the Prime Minister, for example was an associate member of the Carlton Club, which appears in my series. Women were segregated and had their own rooms. The Smoking Room was strictly off limits to women and non-members.

Did your subjects see these works? What were their views of them?

They saw the photographs with texts and generally were impressed by the quality of the prints. They had no issues with the text. Their feedback was generally positive. At one point there was confusion over copyright but this was quickly resolved. As I initiated the project and it was not commissioned, the copyright of all the work belongs to me.

Can you explain a little more about your choices of text and image in both series? Where do the texts come from and why did you choose to work this way?

In Belgravia, texts come from conversations we had. I spent a lot of time with people whom I photographed and would write down or remember key topics discussed. I would keep notes of their conversations, which were then reworked, capitalising key words. The capitalisation used here indicated that the text was not a direct transcription but constructed like the photographs.

I had been reading Benjamin, Brecht, Barthes and film theory, thinking about the idea of ‘distantiation’ as referred to by Althusser as a means of challenging mainstream ideological institutional structures. Of course these structures were ‘family’ and ‘taste’ in Belgravia.

In Gentlemen text became a device to critique patriarchy and its conservative formations. The text here was totally invented, inspired by clubland literature (Dornford Yates, John Buchan, Kipling, Ian Fleming: a fictional voice) and speeches of parliament published in the Hansard section of The Times (historical voice in the past tense). The uppercase letters of words parody the speech acts of public school educated men but also reference irony.

Text adds new meanings that did not exist in the image alone and operates between the text and image. Adding text also prolongs the time that a viewer spends looking and thinking about the work. It slows the consumption of the image.

How did the public and the art world receive both these series at the time?

Critically the work was championed by the French and I had my first solo exhibition in Paris with Samia Sauoma at La Remise du Parc in November 1980. Christian Caujolle, an art critic, championed the work at its beginnings and I had write ups in the French newspapers: Libération and Le Monde. My work was shown during Mois de La Photographie set up across galleries and institutions in Paris to promote and disseminate photography.

Belgravia had appeared in group show called Five Photographers at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London in 1981. Nine images of Gentlemen appeared at Riverside Studios in an exhibition called Beyond the Purloined Image (1983) curated by the artist Mary Kelly. The work was supported by The Arts Council who awarded me a grant, yet it received little critical attention in the UK when it first appeared. Stuart Morgan was the only one to write a supportive review of Belgravia in Artscribe in 1982. Belgravia was included in a group show in 1982 at David Dawson’s B2 Gallery in Wapping called Light Reading .

Generally the early work was respected by British academics. I was invited to lecture on my work at West Surrey College of Art (University for the Creative Arts, Farnham) and other art colleges. Gentlemen was supported by the critic Abigail Salomon- Godeau and this work was shown at PS1, New York in 1983. I earned very little from my work for years and the break through came with Connoisseurs being shown at Riverside Studios in 1986. Finally I was accepted as 0.5 Lecturer in Photographic Practice at London College for Printing and that made the difference in helping me sustain a practice which was experimental and non commercial … in fact; too conceptual for most.

It is not surprising that there are limited reviews now. Things seem to have gone backwards.

Is there a correlation between how it was received then and how it is being received now? i.e. What has changed politically in our society and is it reflected in how this work is consumed?

I think it is not being received and there is a lot of indifference to what it is referring to, i.e. class and male privilege. We live in a more unequal society as the recent BBC series The Super Rich and Us points out.

What does it mean to you to have your work in Tate Britain?

It means a lot to me in that it will be part of my legacy to British culture and hopefully it will be work that might interest future artists and their research.

It documents a particular age in the UK (1979-1983) which became the beginning of the end of an egalitarian project which included the Civil Rights Movement in the early 1960’s and the Equal Pay Act of 1970, Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the Feminist and Gay movements. President Obama recently pointed out in a speech that social mobility had also decreased in the USA.

What are your hopes and aspirations for your career from this point? How do you define success?

Although I am getting older, I have every intention of working on new projects that challenge me mentally and physically and I have quite a few lined up.

Presently I am working on a series of performative portraits of Japanese women called Karyukai (2) and a series of works addressing folk culture and animal life in Japan called Monogatari (3). Exhibitions are planned for November 2015 at Filles du Calvaire and in 2016 at Grimaldi Gavin. I will be participating in art fairs globally including Paris, London, Delhi etc.

In 2016 I am planning a road trip across America, focusing on the Midwest with an aim to understanding and researching this part of America that my mother left to come to Europe in 1946. I hope to make this trip with Anna Fox whom I mentioned the idea to at Paris Photo last November.

Success is having enough money to be independent and enough to share with the community that nurtured you.

The success of the India Song series helped finance my studio, rented from Space studios, and to finance Chandelier Projects from my studio since September 2013. I became patron of several art organisations who had helped me in the past.

You are involved in Fast Forward, a conference at Tate [in Autumn 2015] discussing prominent issues regarding women in photography. What is your main hope for this conference?

That we help define what are the main issues confronting women photographers today and help connect and expand new networks to help each other.

What would you advise women working in photography today?

Connect with other photographers and artists; establish strong bonds and new networks using the social media and the internet to disseminate your work.

Challenge your comfort zone, take risks, learn new skills, update and push the boundaries, experiment.

__________

Notes:

(1) Suburbia, is the titled of a self published book of documentary photographs taken in the early 1970’s by Bill Owens whilst working as photographer for the Livermore California Independent . The book celebrates the American Dream and the suburban life style . The book is about his friends and their pride in having achieved material success .The book is very funny no irony or critique was intended.

(2) Karyukai refers to the elegant high culture of the Geisha. The “flower and the willow world” which also appear in the famous Ukiyo-e wood block prints produced in the 17- 19th century by artists such at as Utamaro and Hiroshige. It is a matriarchal society run by women although there are male geishas. Women are apprenticed and live in okiya and train in various Japanese arts such as classical music, dance, conversation mainly to entertain male customers.

This photographic work alludes to a contemporary version of this separate reality which still exists in Japan today. Women perform femininity with traditional kimonos. Each photograph is accompanied by a poem in Japanese composed by the subject.

(3) Monogatari are tales, an ancient Japanese literary form of which there are several genres prominent in the 9th to 15 th century. My photographs reference spirits or kaidan which take the form of animals. Popular tales from Japanese folklore became performed in Kabuki (Japanese classical dance drama from the Edo period) Noh and Bunraku.